Why are we so obsessed with Japan’s cherry blossoms?

In the Philippines, where majority of the land is inhospitable to the stunning tree, the search for our own sakura is on. And it has to stop

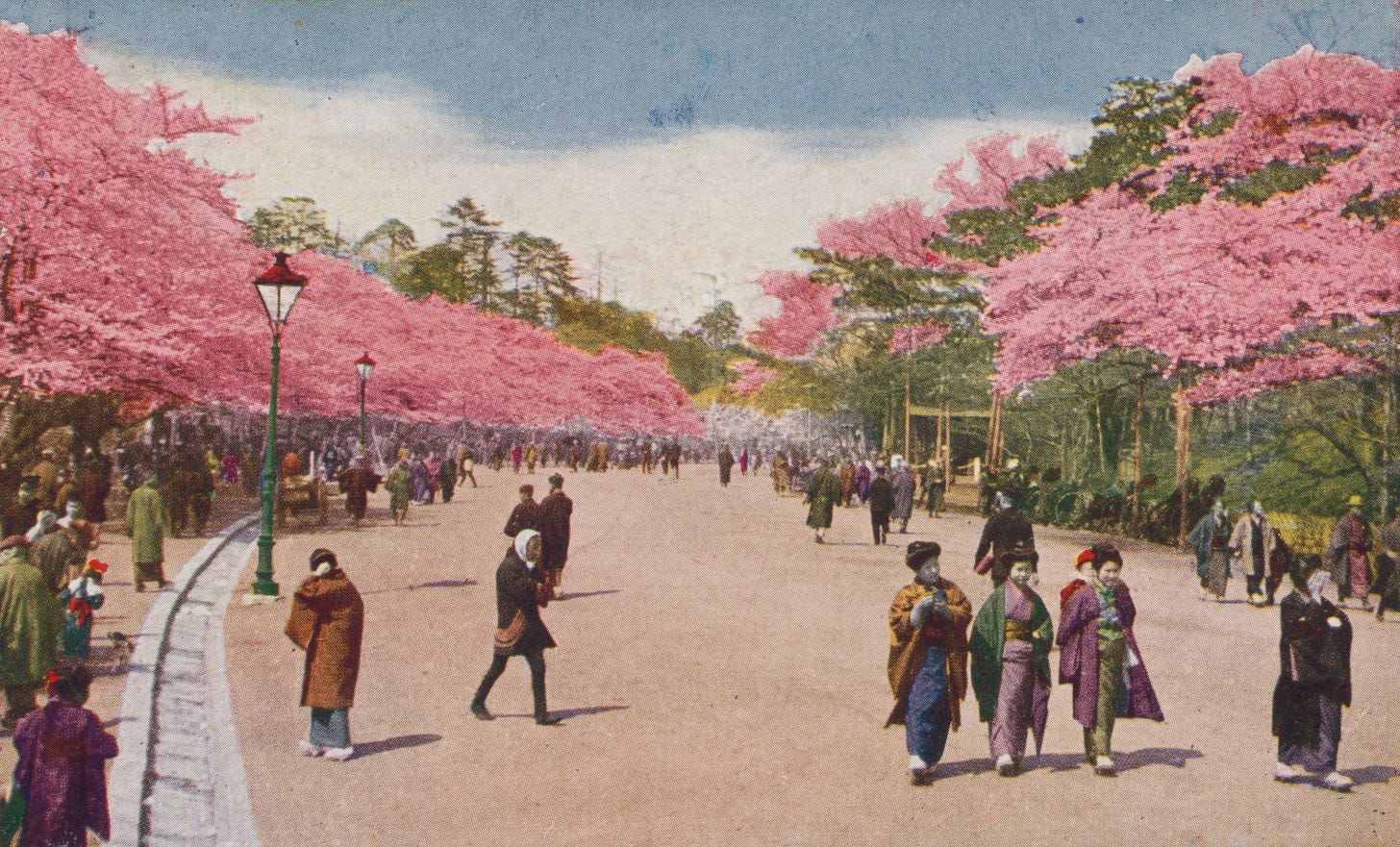

Single cherry blossom at Ueno Park (Flower season at Tokyo) (Tōto no Hana) Ueno Kōen no Sakura. Postcard, [between 1920 and 1940]. Downloaded from Library of Congress on Unsplash

In February, around the time of writing this article, the winds were at its coldest. Leave the window ajar and the wintry air from Siberia delivered by amihan (northeast monsoon) would creep in. If the human responds to the cold by curling up in bed and covering themselves in a cocoon of fabrics, a towering tree, standing as tall as ever somewhere out in the open, awakens tender scarlet blossoms on its bare limbs. This tree is locally known as malabulak (Bombax ceiba).

Once the warm gust of wind drifts back in, between March and May, its fiery blooms turn into pods of cotton. Around that period, it’s time for the other Philippine trees, whose leaves, like the malabulak, had been shed off in the previous months, to clothe themselves in an exquisite vestment of delicate blooms. Philippine teak (Tectona philippinensis) in tender purple, salimbobog (Crateva religiosa) in a mélange of cream petals and pink antlers, salingongon (Cratoxylum formosum) in mesmerizing pink, banaba (Lagerstroemia speciosa) in pinkish purples and narra (Pterocarpus indicus) in resplendent yellow.

Among the list of trees described earlier, banaba, along with narra, might be the most familiar. Commonly planted as a roadside tree, it’s also prized for its medicinal properties.

Year after year, the said trees slip out of their green uniform. As if struck by indecisiveness in front of a dressing mirror, they remain in their naked glory until they wrap themselves in their floral cloaks. Then, after a couple of days or even a few weeks, the blossoms wither and the trees put their uniform back on. The splendid display of flowers, like a garment only reserved for the most special occasions, would not be seen until time tells so. And so, the trees wait.

Such magnificent exhibition doesn’t go unnoticed. A passerby would look up and marvel at its beauty. But it’s a fleeting admiration. After a few seconds of stopping by or slowing down their pace, the passerby nonchalantly shifts their gaze back to the road before them. The sight would be a flimsy memory.

Meanwhile, more than 3,000 kilometers away from our archipelago, around the same months when several Philippine native trees are blooming, there is also a tree species that does the same. Their leaves fall, their intricate branches exposed to the cold, then they flower. And in the fullness of their immaculate revelation, this tree commands devotion instead of mere attention: People plan their trips around it, they set out for picnics in parks and they linger, knowing that the presence of these dainty blooms won’t last long. Such is the power of Japan’s cherry blossoms (Prunus spp.) or sakura.

It is not only in Japan that cherry blossoms are revered. In the Philippines, where majority of the land is hospitable to over 10,000 plant species but not to the much-coveted Japanese tree (except in the mountainous region of Benguet where cherry blossoms were introduced in 2016), the ornamental cherry tree has a very special place in our consciousness, so much so that it has set the standard for flowering trees.

When we don’t know what something is, we define it by associating it with what is familiar. In fact, many native trees have local names that bear the prefix mala. Malabulak, for example, got its name because it produces cottony pods. There’s a tree called malabayabas (Tristaniopsis decorticate) whose vividly mottled trunk looks similar to that of guava (Psidium guajava), a species introduced from South America. And even if our interaction with sakura is only through anime, photographs, or maybe artificial versions found in malls, it has become a reference point when defining flowering trees.

Before an observer realizes the identity of a tree in bloom, they inevitably hark back to the sakura’s pristine appearance. To find the likeness of cherry blossoms in a tree is an affirmation of beauty. It is only then that we arouse infatuation towards certain species.

In the summer of 2018, for example, a tree growing in the parking area of a university in Cavite was the talk of (Facebook) town. Its crown was smothered in pink, leaving no room even for the tiniest bit of green growth. The tree isn’t herculean in size; it’s tall but just enough to conveniently fit it in a photograph. Amid impermeable concrete and hot shiny cars, spent blooms pooled under its canopy breaks the monotony of the unnatural.

The tree went viral not for what it is, but for its supposed semblance with the cherry blossom. Media outlets like Esquire Philippines and Rappler picked up the story, each of them placing “cherry blossoms” in their respective headlines. After all, what matters is its likeness to the celebrated tree of Japan more than its identity. The tree in question, as these sites pointed out, was a potentially invasive tree introduced from South America called Tabebuia rosea.

Even when we attempt to reacquaint ourselves with our native trees, we still turn to the cherry blossom, as if the foreign tree fetches long-forgotten memories from the deepest crevices of our brains.

Japan’s cherry trees are stunning. There’s no doubt in that. They produce the kind of blossoms that aren't just pretty but also fragile. With the gentle hues of most species and cultivars, the sakura is rarely cloying or hot to the eyes.

British ornithologist and sakura expert Collingwood Ingram, who is the subject of the book “The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan’s Cherry Blossoms” by Japanese journalist Naoko Abe, attributed his enchantment for the cherry blossom to its “refined charm…and a delicacy of color and form that appeal to one’s aesthetic sense that others can never do.”

But how did the humble cherry tree reach such status?

Becoming the icon of Japan

Photo by kazuend on Unsplash

The cherry blossom isn’t just a mere object of desire for the Japanese. It is a character intrinsically woven into their collective consciousness, so much so that it has become a pillar of Japanese identity. And it was a deliberate choice to elect the sakura as such.

Before the reign of cherry blossoms, ume, or plum, was the subject of hanami, which translates to “flower viewing.” It’s also a dominant image in Japanese literature then. In a compilation of poetry from AD 759 called “Man'yōshū” or “The Collection of Myriad Leaves,” the oldest extant collection of classical Japanese poetry called waka, ume is said to be mentioned more often than sakura. As the Japanese writing system then was still largely influenced by that of the Chinese, it was perhaps also inevitable to borrow the imagery of ume—a more ostentatious flower favored by the Chinese.

Writing about the origin of the Japanese appreciation for cherry blossoms, T Magazine editor Hanya Yanagihara suggests that choosing cherry blossoms over plum is “a way of culturally asserting themselves.”

In AD 812, the imperial family held the very first sakura viewing party. At first, it was only accessible to aristocrats who had private gardens. It was only during the Edo Period, when cherry trees were painstakingly cultivated and widely planted in public spaces, that sakura viewing became a much more public affair. It was also during this period that Japan experienced over 220 years of seclusion called Sakoku. Abe notes this period as the golden age of cherry blossoms.

Perhaps it was also during this period that the sakura fastened its claim as an icon of Japan. And even when American Commodore Matthew Perry harassed Japan to open its doors in 1853, the cherry blossom remained a tenacious reminder of the Japanese identity.

“Japan without the cherry blossom is like a person without a head,” Yanagihara writes. “The cherry blossom is not just an icon of Japan: It is the icon of Japan, one that enhances and ultimately eclipses every other.”

At one point, the cherry blossom and the Japanese were considered one and the same. “If someone wishes to know the essence of the Japanese spirit, it is the fragrant cherry blossom in the early morning,” a line from a poem written in 1791 by Japanese scholar Norinaga Motoori reads. But the interpretation of Motoori’s poem, especially during the Pacific War from 1941 to 1945, was shrouded in bleakness: The oneness of the sakura and the Japanese people took a grim turn.

Beginning in the late 1800s, the sakura was propagandized and militarized. The sakura lovingly imagined as the Japanese spirit became a maligned justification of death. “We don’t rejoice over the blossoms, we rejoice over the flowers’ falling and their heroic attitude,” Abe quotes Kiyoshi Hiraizumi, a professor of Japanese history at the Tokyo Imperial University who, according to Abe was instrumental in spreading this concept of the Japanese spirit by giving “spiritual lectures” to the military and police as well as students. It was this analogy that led a group of Japanese aviators known as kamikaze to commit suicide attacks.

“It became the norm to believe that the Yamato damashii, or ‘true Japanese spirit,’ involved a willingness to die for the emperor—Japan’s living god—much as the cherry petals died after a short but glorious life,” Abe writes.

Even with this dark bit of history, the Japanese were able to reclaim the symbolic meaning of the cherry blossom.

Today, the sakura is a reminder of impermanence: mono no aware, they call it. “A sakura is the human life condensed into the period of a week: a birth, a wild, brief glory, a death. It is to us what we are to the sweep of time—a millisecond of beauty, a memory before we are even through,” Yanagihara writes.

The rich history attached to it gives the cherry blossom its weight, naturally evoking memories wherever the wind takes it.

Natural selection

The Philippines collectively didn’t give such high regard to a certain natural object the way the Japanese adored the cherry blossom. To begin with, it would be hard to single out a species from the 9,500 plant species naturally occurring in our archipelago, and much harder to find just one that would be deemed culturally significant in every region. So, our desire for the cherry blossom isn’t just a search for beauty. Instead, it could be an effort to assimilate the culture the Japanese have built around the stunning flowering tree.

Much of our collective consciousness was informed by abuse. Unlike Japan’s 220 years of peaceful seclusion, the Philippines was under colonial rule for almost 400 years. Not only is it a time of human oppression, but the forests, too, were plundered. They were cleared to give way for settlements, agriculture and other industries. And even our spiritual practices were taken away from the natural landscape and contained within formal structures of worship. In such turbulent times, who would fancy a singular natural entity to embody the Filipino spirit?

It’s estimated that forest cover in the Philippines declined from 90 percent in 1521 to 70 percent after the Spanish Colonial Rule. Although our forests didn’t lose their mystical traits, they were valued and eventually plundered for their utility. Molave (Vitex parviflora), for instance, were logged to build their ships. Americans, too, looked at our lands as a source of limitless resources: “The wood of the Philippines can supply the furniture of the world for a century to come,” an American senator said in 1900.

That mindset perhaps explains why the Americans introduced the invasive mahogany (Swietenia spp.), which inhibits the growth of surrounding species, to our lands in the early 1900s. One could argue that the settlers started growing mahogany here for its utility. The species would persist even in reforestation programs because of its economic value.

The ecological imprint the settlers left also includes trees that are often used as public space vegetation. It would be easier to find exotic (and potentially invasive) species like caballero (Caesalpinia pulcherrima) and African tulip (Spathodea campanulata) than, say, Siar (Peltophorum pterocarpum). Introduced from South America during the Spanish Colonial Period, caballero could produce a high number of seeds that germinate and grow fast. Meanwhile, African tulip, which came to our land in 1925, could not only reproduce quickly, but its flowers can lure and kill bees. Both trees are utilized as ornamental specimens because of their flowers.

When the time came for us to find an emblem from our diverse flora, it was possibly informed by the adversities our nation experienced. In 1934, over a year before national leadership was given to a Filipino, American Governor-General Frank Murphy proclaimed narra as the Philippine national tree.

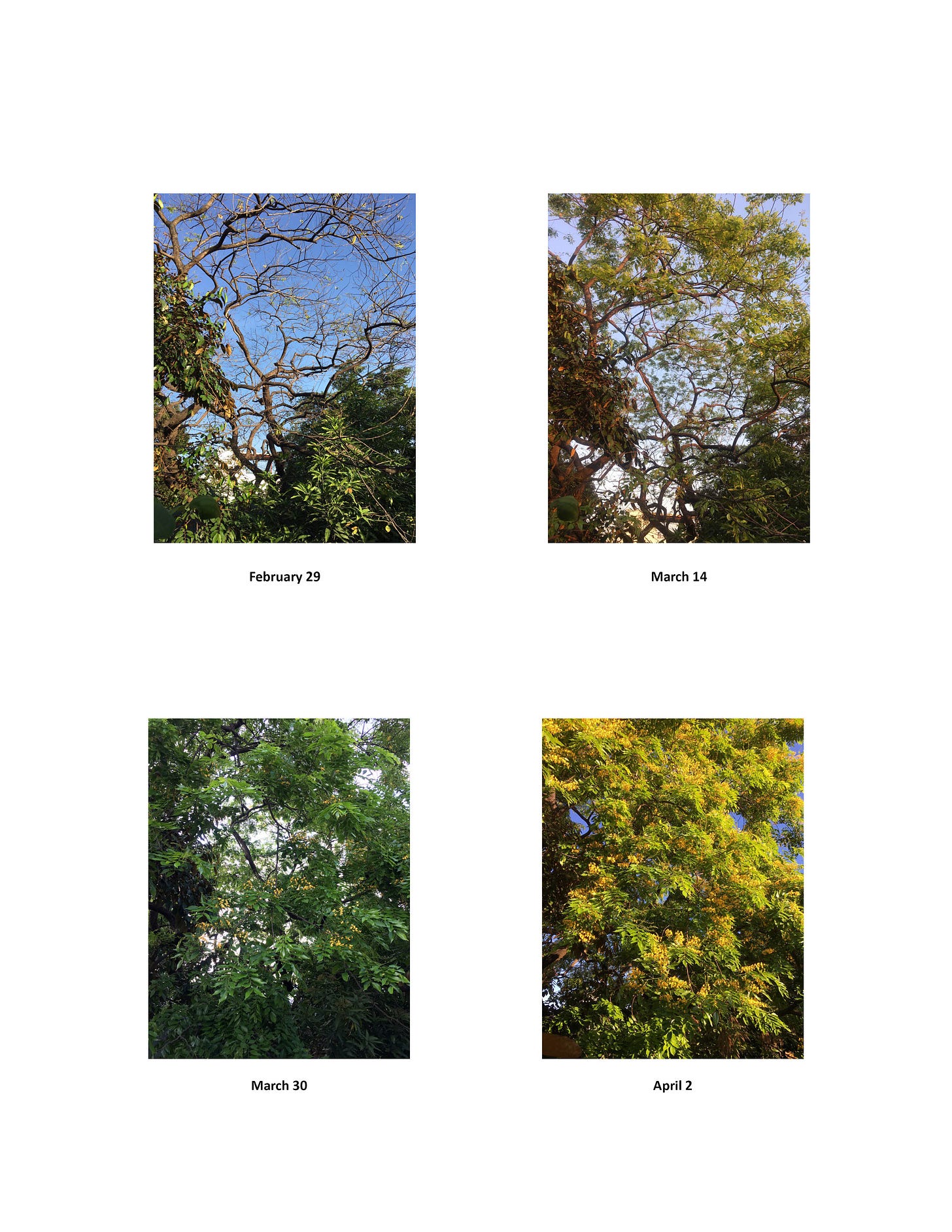

Narra’s defoliation stage to flowering, as observed this year

Narra, like most species from the leguminous family, can capture atmospheric nitrogen and store it in its root system, allowing them to survive even in infertile ground. The tree is also typhoon-resistant, and its strong timber is prized in construction. Aside from the fact that narra is widely distributed in the country—apalit and naga are both regional names for narra—it allegedly became a national symbol because its durability demonstrates Filipino resilience. And after our country’s traumatic colonial past, at a time of our independence from the shackles of colonialism, it might have been inevitable to find a tangible symbol for a vital trait that enabled our country to endure hundreds of years of oppression.

There’s virtue in finding Filipino resiliency in a majestic tree. But thinking about it now, it also seems ominous. Was it a way of acknowledging that there will be more to endure? That resilience would be our defining trait again and again and again?

Resiliency would again be appropriated at one point during the almost decade-long and still ongoing campaign for the declaration of waling-waling as a national symbol.

It was in 2012 Reps. Mylene Garcia-Albano of Davao and Marlyn Primicias-Agabas of Pangasinan filed House Bill No. 5655 to push for the recognition of the waling-waling (Euanthe sanderiana) as a national flower. If anything, it seemed the right thing to do. The current national flower, which was also declared by Murphy in 1934, is not indigenous to the Philippines. And so, the waling-waling, an orchid species endemic to the forests of Mindanao, is deemed well-suited to represent the Filipino identity.

The proposed bill, however, was vetoed by then President Benigno Aquino III the following year. “Declaring the waling-waling orchid as the second national flower would have the effect of displacing the hallowed status of sampaguita, a cherished national icon as the primary symbol of Philippine culture and artistry,” he said. “There are other means to promote the protection and preservation of the waling-waling orchid without declaring it a second national flower.”

In 2016, Garcia-Albano introduced House Bill No. 1561, again, in hopes of making the waling-waling a national flower. Her explanatory note reads, “The majestic plant perched atop a tall tree enjoying the elements of the earth [symbolizes] the high aspirations of the Filipino. The Waling-waling is never [selective] in its growing environs…Such quality can be a symbol of the resiliency of the Filipinos.”

Until today, the waling-waling isn’t an official national symbol yet. Before the end of 2019, the House of Representatives passed House Bill No. 4952 to declare the orchid as a national symbol. This time, instead of considering it a national flower, the latest bill seeks to declare it as the national orchid.

Finding sakura in the tropics

At one point, the quest for the Philippine equivalent of the cherry blossom had reached a fruitful end.

Since 2004, the city of Puerto Princesa has been celebrating a festival with balayong at the center of it. Balayong, which is also another local name for tindalo (Afzelia rhomboidea) in some regions, is a kind of tree whose blooms in hues of pink and cream approximate those of Japan’s cherry trees, thus earning the name Palawan cherry.

The tree, however, has an obscure history. One, it is not a cherry. Two, it’s possibly an exotic species. The late botanist Leonard Co, as cited in stories written about the tree, identified balayong as a Cassia species or cultivar that was introduced to Palawan.

In his observation, Patrick Gozon, an architect who keeps a blog on native trees, observed that a lot of balayongs in Palawan are found in inhabited places. “I asked one local if the trees in their area were natural, he said most of them were planted when they paved the main highway. They are even sometimes dispersed with mahoganies and knife acacias which also are truly non-natives of Palawan and the Philippines,” reads his blog.

To search for the Philippine version of the cherry blossom is a futile exercise. There are several Prunus species naturally found in Philippine forests. But unlike its Japanese relatives, the flowers of these species are rather inconspicuous. Their plainness might be more attractive to wildlife than to humans. And perhaps there is something to learn from wild birds that feed on whatever nature offers: That, like them, we must learn to appreciate our native flora for what they are.

In the book “How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy” by Jenny Odell, an educator, a writer and an artist whose “medium is context,” oddly and amazingly places the narrative of idleness in the context of the predominantly environmental concept of bioregionalism.

“Bioregionalism,” which was articulated by the late environmentalist Peter Berg in the ’70s, “is first and foremost based on observation of what grows where, as well as an appreciation for the complex web of relationships among those actors,” she writes. “More than observation, it also suggests a way of identifying with place, weaving oneself into a region through observation of and responsibility of the local ecosystem.”

To define our bioregion based on geography is to acknowledge that there is a natural relationship among indigenous entities—wildlife and flora, flora and fungi, fungi and bacteria, and so on—established in that specific place. Thus, the introduction of a new species could possibly disrupt that web of connections.

In an interview for an article I wrote in 2017, native flora enthusiast Ronald Achacoso says, “You cannot fully appreciate a plant or an organism by isolating it and looking at it apart from its natural environment. If we could see the whole assemblage and how one native species is intricately connected to another, then we get to see the beauty beyond the visual or aesthetic level. Then we truly see how beautiful something is in its proper context.”

If there is anything that we could learn from the way the Japanese see the cherry blossoms, it is their practice of reflection, of looking within and recognizing natural order. We can’t just borrow such symbol; it wouldn’t mean anything to us. But we can give the same high respect to what have always been here.

As of writing* this article, the narra in our neighbor’s yard is once again naked. In a couple of weeks, its tiny fragrant flowers would cover the street with patches of yellow. Everything would be smothered in yellow. Then, the yellow would become a memory. Everything would be just as they are: the narra’s crown green and the pavement gray. But there is an assurance that there will be another rain of yellow in the next year and the year after that. Again and again. As long as time tells so.

*This was written in February. As of now, after flowering multiple times between March and April, the narra tree is beginning to produce prickly pods. These will be ready for planting during the rainy season.

**I wish I could tell you more about the other trees I described earlier, but narra is the most accessible right now. While I made plans of observing the flowering of those trees this dry season, Covid happened. There’s still next year, though!

I enjoyed reading your article, specially for your description of some of our native trees. However, I would like to clarify your paragraph about Palawan Cherry. The name Balayong is used for two different trees: the Palawan Cherry and Tindalo. Tindalo, as you indicated has scientific name Afzelia rhomboidea. Its leaves are pointed and bigger than that of Palawan Cherry and its flowers are colored light green. Meanwhile, Palawan Cherry is a species of Cassia. Its leaves are oblong and its flowers are colored pink. I have not read anything which explains why these two different tree species are both called Balayong, but that unfortunately is the case and leads to some confusion.